1997-present

20 Years of Serving the Community

From the beginning, Spectrum Health has been shaped by its mission: To improve the health of the communities we serve. That was the impetus for bringing together Blodgett Memorial Medical Center and Butterworth Health Corporation 20 years ago and continues to guide us today.

These milestones help tell the story of our integrated health system and the rich legacy we continue to build.

Spectrum Health is formed after a 1996 decision by the U.S. District Court, which approved the merger of Blodgett Memorial Medical Center and Butterworth Health Corporation.

Spectrum Health Healthier Communities is established. The system dedicates $6 million annually in perpetuity to support programs and services for underserved residents in West Michigan.

Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children's Hospital performs West Michigan's first pediatric bone marrow transplant.

The Spectrum Health Renucci Hospitality House opens next to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital. Funded by a donation from Mr. and Mrs. Peter Renucci and a successful capital campaign, the Renucci House is a home away from home for families of hospitalized patients.

Richard C. Breon joins Spectrum Health as the system's new President & CEO. He sets the vision for Spectrum Health.

Healthy Lifestyles launches as the Employee Wellness Program, encouraging employees to make health and wellness a priority.

Spectrum Health implements the Cerner health information technology system to combine patient electronic medical records at Spectrum Health Butterworth and Blodgett hospitals into one system.

Spectrum Health Grand Rapids is named 2001 Top 100 Integrated Healthcare Networks by Thomson Reuters (later becoming Truven Health Analytics®).

United Memorial Health System in Greenville joins Spectrum Health, bringing Spectrum Health United Hospital and Spectrum Health Kelsey Hospital into the system.

Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center opens, bringing together the expert cardiovascular programs from Spectrum Health Blodgett and Butterworth hospitals and creating an environment for the program to achieve national prominence. This new state-of-the-art facility was built with $35 million in gifts from more than 3,000 donors.

Priority Health is the first company in West Michigan to offer a Medicare Advantage plan with prescription coverage.

Spectrum Health enters an alliance with Michigan State University College of Human Medicine to help build and develop a new medical school campus in Grand Rapids. Spectrum Health commits $55 million to the $90 million project, which includes principal and interest payments on the building for 25 years. Private donations were raised, with first naming gifts of $20 million donated by area business leaders, including alumni Ambassador Peter F. and Joan Secchia, for whom the Secchia Center is named.

The da Vinci® Surgical System, a robotic device for minimally invasive surgeries, is purchased by Spectrum Health with the support of a $1 million donation from Mr. and Mrs. Tom Fox.

2007-2012

Priority Health purchases Care Choices HMO, Care Choices PPO and Preferred Choices PPO health plans and becomes the state's 2nd largest health plan. Priority Health and Care Choices both were recognized nationally for delivering high-quality health care services to members and providers.

Spectrum Health Lemmen-Holton Cancer Pavilion opens as a hub for comprehensive outpatient cancer services, providing the majority of cancer patients in the area with a serene environment for hope and healing. A gift from Rich and Helen DeVos in 2002 enabled Spectrum Health to purchase the property for the pavilion. It was named by Fred and Lena Meijer, who made the lead gift for the facility, to honor the service and community stewardship of three friends: Harvey E. Lemmen and Earl and Donnalee Holton. A special gift from Bill and Sharon Lettinga helped support the underground connector, which is used for patients to be transported in privacy from the Spectrum Health Cancer Center Lettinga Inpatient Cancer Center for treatments at the pavilion.

Spectrum Health Medical Group is formed to bring more coordinated, seamless care to patients. Today, it is one of the largest and most comprehensive multispecialty physician groups in West Michigan, with 1,600 physicians and advanced practice providers.

Spectrum Health Blodgett and Butterworth hospitals and Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital earn Magnet Recognition® status from the American Nurses Credentialing Center, the gold standard for nursing excellence. Adherence to best practice standards provided the conceptual framework for the Spectrum Health Magnet journey, which involved years of work to improve patient care, patient safety and patient experience.

The Spectrum Health Foundation shifts focus from capital investments to patient programs and services, including in the Frederik Meijer Heart and Vascular Institute, the Richard DeVos Heart and Lung Transplant Program, the Haworth Family Pediatric Oncology Innovative Therapeutics Clinic, the Blood and Marrow Transplant Program for adults, the Congenital Heart Center at Helen DeVos Children's Hospital, and the Peter and Joan Secchia CarePartners Program. Since 1997, philanthropic support provided gifts totaling more than $408 million. In the early years of Spectrum Health, much of that support created facilities including the Renucci Hospitality House, Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center, Cancer Center at Lemmen-Holton Cancer Pavilion and Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital; and in our regional hospitals, the Hendrik and Gezina Meijer Surgery and Patient Care Center, the Spectrum Health Reed City Hospital Susan P. Wheatlake Regional Cancer Center and a new emergency department at Gerber Memorial Hospital.

Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital opens its new four-story, 158,000-square-foot patient care addition. The hospital houses 284 private rooms, 14 operating rooms, and renovated nursing units and public spaces.

Gerber Memorial Hospital in Fremont joins Spectrum Health. The hospital becomes Spectrum Health Gerber Memorial.

Priority Health enters the consumer market by introducing MyPriority®, a health insurance plan for individuals in Michigan. This business has grown to 118,000 individual members in seven years.

Spectrum Health performs its first heart transplant and makes it possible for patients to receive this lifesaving care close to home.

Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital opens a new facility, marking a new era in children’s health care in West Michigan. The new facility was built thanks to $103 million in generous community support. More than 6,000 donors contributed to the new $286 million building. The children's hospital originally opened in 1993.

Zeeland Community Hospital joins Spectrum Health. The hospital becomes Spectrum Health Zeeland Community Hospital.

Spectrum Health University is established to provide best-in-class learning opportunities to our employees and providers.

Priority Health's HMO plan is recognized as Michigan's essential health benefits benchmark plan by the Michigan Department of Insurance and Financial Services.

The "MyHealth" patient portal launches to provide consumers with convenient access to their health information. Today the portal has 490,000 members.

Spectrum Health Medical Group opens Spectrum Health Integrated Care Campus – Holland. The facility sets a new standard of care with access to multiple specialties under one roof, working in tandem with local providers, regional hospitals and other facilities.

2013-2017

Spectrum Health successfully performs the first lung transplant in West Michigan, expanding access to such specialized care close to home. Later that year, Spectrum Health performs West Michigan's first combined heart and lung transplant.

Memorial Medical Center joins Spectrum Health in October. The hospital becomes Spectrum Health Ludington Hospital.

Spectrum Health holds the first Candid Conversations to raise awareness about breast cancer. The event draws 2,000 breast cancer survivors, family members, friends and supporters who open pink umbrellas to show their support by making a giant breast cancer “Ribbon of Hope.”

Mecosta County Medical Center joins Spectrum Health. The hospital becomes Spectrum Health Big Rapids Hospital.

Spectrum Health Medical Group opens Spectrum Health Integrated Care Campus – East Beltline, the system's second integrated care campus, in Grand Rapids.

Spectrum Health and Holland Hospital establish the Forum for Hospital Collaboration to develop projects that improve the quality of health care while providing value to businesses in the communities they serve.

MedNow™ launches in 2014, giving patients fast, convenient and affordable ways to receive care by connecting to Spectrum Health physicians and advanced practice providers through a smartphone, laptop or computer.

Pennock Health Services in Hastings joins Spectrum Health in May. The new entity becomes Spectrum Health Pennock.

Meijer Inc. opens a full-service retail pharmacy at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, becoming one of the first major retailers to open a pharmacy within a large hospital system in Michigan.

Priority Health introduces the Cost Estimator to provide consumers with knowledge and choice when planning health care procedures. It is the first health plan in Michigan to make health care pricing available to consumers.

Spectrum Health’s adult blood and marrow transplant program reaches another milestone when it performs its 200th transplant on December 31, 2015. The adult program, supported by philanthropy from the community, began performing transplants in February 2013.

Spectrum Health opens the system's first Convenient Care Walk-In Clinic in Greenville to provide an alternative to the emergency department for low-acuity primary care.

The new Spectrum Health Rehab and Nursing Center - Kalamazoo Avenue opens. The facility serves 700 patients each year and is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities with specialty program accreditation in brain injury and stroke.

Spectrum Health is selected as part of a consortium of health systems to participate in a groundbreaking research effort aimed at advancing personalized health care. The All of Us initiative is funded by the National Institutes of Health. In total, Spectrum Health researchers today receive roughly $36 million per year in research support from public and private grant sponsors.

Spectrum Health receives the 2016 Foster G. McGaw Prize for Excellence in Community Service, one of the most revered community service awards in health care, for its programs and services to reach the underserved residents of West Michigan.

STR!VE, a unique health membership concept, launches in July to help local employers and residents optimize health and wellness.

Select Specialty Hospital – Spectrum Health opens on the Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital campus. The long-term acute care hospital is a joint venture between Spectrum Health and Select Medical Corporation and replaces the Spectrum Health Special Care Hospital on Fuller Avenue.

Aero Med Spectrum Health celebrates 30 years of life-saving flights for patients of West Michigan.

Spectrum Health and Meijer Inc. continue their collaborative efforts with the launch of co-branded over-the-counter products in 23 stores, offering 22 common over-the-counter products. Spectrum Health will allocate 100 percent of its proceeds from the products to benefit Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Priority Health membership grows to nearly 800,000 members. It is the second largest health insurer—and the fastest growing—in the state.

Spectrum Health is named one of the 15 top health systems and one of the top five largest health systems in the nation by Truven Health Analytics®, based on key performance measures. This is the sixth time since 2010 that Spectrum Health has received this honor.

1873-1918

It Began With an Act of Charity.

Scientists and physicians introduced the modern germ theory of disease in the 19th century. They made it possible to identify both the cause of infectious diseases and how they spread. However, at the end of the century, "wonder drugs" were still unavailable to treat these diseases. And there were no diagnostic tests to see inside the body and determine the physical, chemical and biological effects of disease.

Most health care took place at home. Doctors only were called upon for life-threatening illnesses or accidents. At the time, nursing was one of the few respectable occupations for women. Trained private duty nurses were paid $15 a week and expected to be on call 22 hours a day.

By 1890, Grand Rapids was a growing city with 50 factories, 40 hotels as well as breweries, foundries, sawmills and flour mills. Health concerns included typhoid, dysentery, influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis, acute streptococcal infection, scarlet fever and diphtheria. Surgery was required for gunshot wounds, broken limbs and injuries sustained at sawmills.

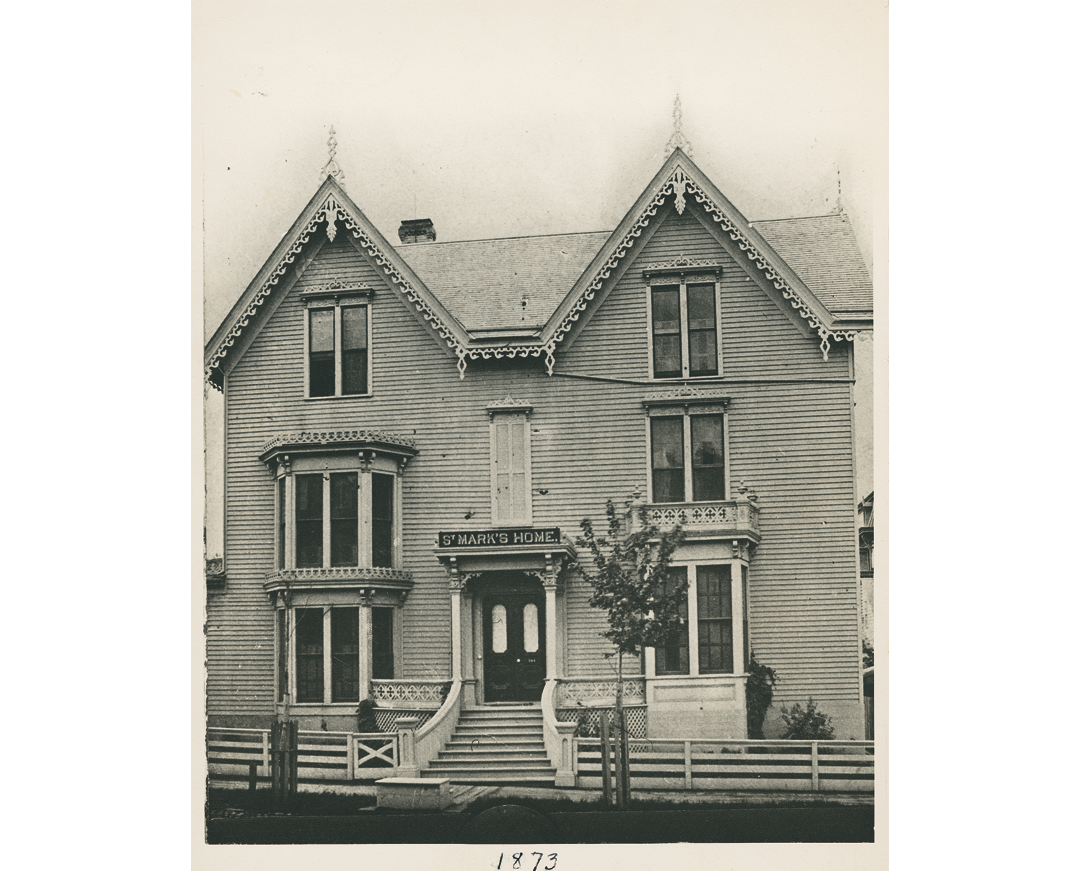

Eight years after the Civil War ended, the women of St. Mark's Episcopal Church established St. Mark's Church Home to care for elderly, homeless and ill parishioners. Mr. and Mrs. Edward P. Fuller loaned a small, furnished house where the women could carry out their work. The Home had accommodations for six people and was soon full.

St. Mark's Church Home was renamed St. Mark's Home and Hospital. Thanks to a donation by the Fuller family, it was relocated to a larger building on 144 Island (Weston) St. Alonzo Platt, MD, was the first house physician and reported that in the first year, there were 148 people seen, 30 admissions and seven births.

Richard Edward E. Butterworth, a member of St. Mark's Episcopal Church, donated the site at the corner of Michigan Street and Bostwick Avenue for a new hospital. Two months after this initial gift, Richard Butterworth died, bequeathing an additional endowment of $15,000.The value of his contributions to the hospital totaled $41,500.

The recently completed 100-bed hospital employed a medical staff of 20 physicians and surgeons. Major clinical divisions included medicine; surgery; obstetrics; gynecology; pediatrics; eye; ear; nose and throat; and pathology.

The new hospital had a sky-lit operating room on the third floor and a hand-cranked elevator, which served a dual purpose. With no house telephones, staff called up and down the shaft to each other. The total cost of the new building was $48,000.

Reuben Petersen, MD, a graduate of Harvard Medical College in 1889, was recruited as superintendent and secretary of the new St. Mark's Home and Hospital. In the first year, admissions jumped to 290 patients.

St. Mark's Hospital Training School of Nurses was founded. Once accepted into the diploma program, nurses had to complete 700 hours of theoretical and practical instruction. They were immediately assigned to the wards and learned patient care by observation. Instruction also included preparing, cooking and serving food to the sick. Alice G. Symonds, a graduate of Boston City Hospital and an experienced surgical head nurse, was the first principal.

The first nursing graduation ceremony was held in St. Mark's Episcopal Church. Six women received their diplomas. Three went on to serve in the Red Cross during the Spanish-American War of 1898.

George and Esther Kendall donated funds to build a new nurses' residence called Kendall Home for Nurses.

St. Mark's Home and Hospital became a secular institution and was renamed Butterworth Hospital in honor of its benefactor.

The first interns were accepted for training.

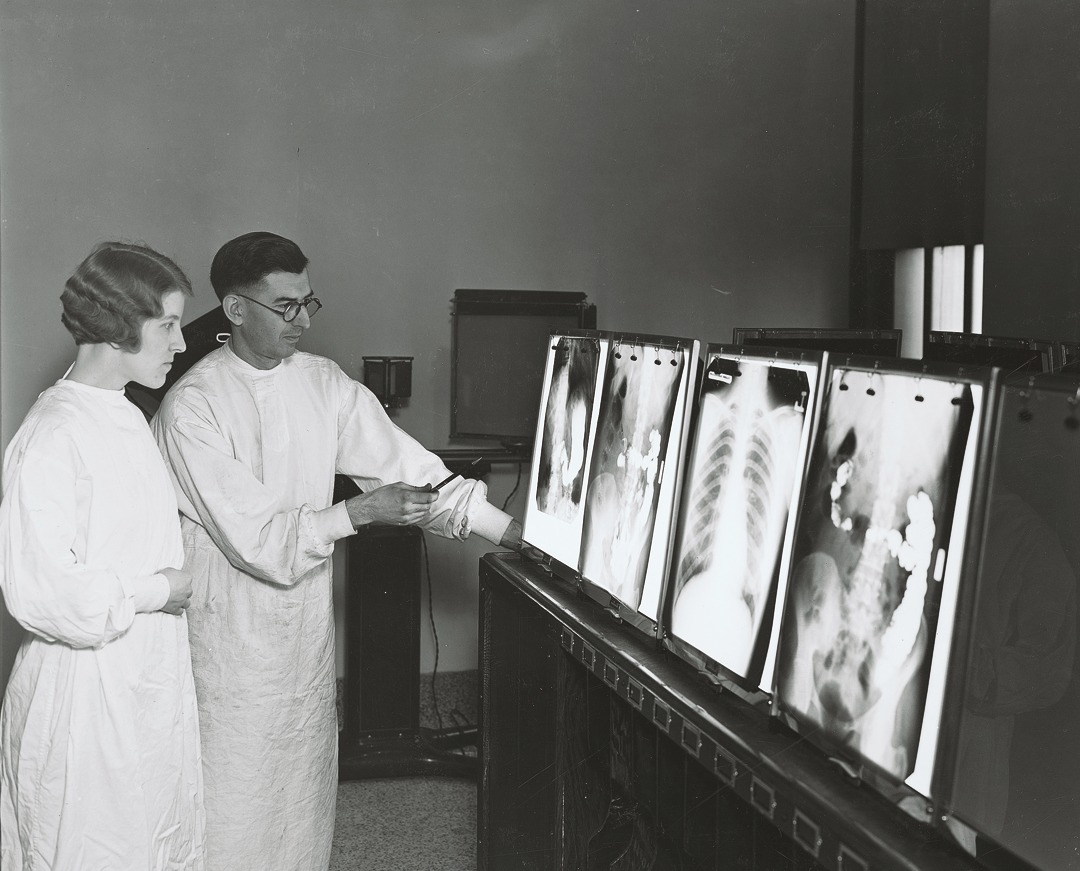

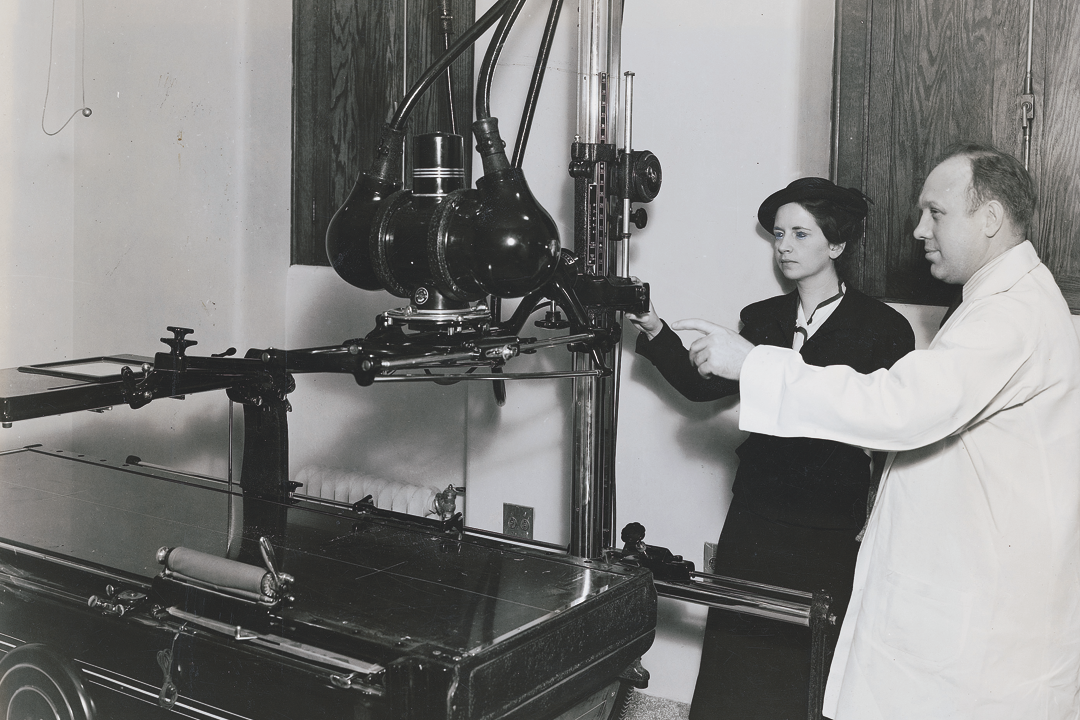

The first laboratory was established with a microscope donated by Herbert M. King, MD, and an X-ray machine from Henry Hulst, MD, one of the first roentgenologists (X-ray specialist) in Michigan.

A telephone system and an electric elevator were installed.

Edward Lowe, Richard Butterworth's grandson, and his wife, Susan Blodgett Lowe, bought, remodeled and donated three cottages next to the hospital for maternity and medical patients, and additional housing for nursing students. Susan Lowe was the sister of John Wood Blodgett, founder of Blodgett Memorial Hospital.

Hospital capacity increased to 98 beds. A free outpatient clinic, called a dispensary, opened.

St. Mark's Hospital Training School of Nurses increased enrollment to 45 students.

Upon the recommendation of the City Health Officer, and to help prevent the spread of disease, the hospital was connected to city water.

The Lowe family donated the Golden Rule Cottage at Ransom Avenue and Michigan Street to house pediatric patients.

With the purchase of two more cottages, Butterworth Hospital grew to 10 buildings and 150 beds. It also became a member of the American Hospital Association.

An outbreak of smallpox in Grand Rapids forced the hospital to take precautions by not accepting new patients.

The hospital acquired its own X-ray equipment.

The United States entered World War I, and many nurses and doctors joined the military. To replace these nurses, class size at the nursing school increased to 40 students per year.

The influenza epidemic reached Grand Rapids shortly after Armistice Day. Hospital staff began working seven days a week.

A registered pharmacist was added to the hospital's services.

A new clinical laboratory was added.

1919-1950

Modern Medicine Emerges

The first decades of the 20th century brought the discovery of insulin, penicillin, and vaccines for diphtheria, pertussis, tuberculosis and yellow fever. Grand Rapids became the first U.S. city to add fluoride to its drinking water.

World War I and World War II were catalysts for innovation that changed the future of medical and nursing practice. Deaths were reduced with the use of sulfa on wounds, Atabrine® for malaria and dried blood plasma for transfusions. Medical evacuation procedures, advanced surgical techniques, the use of morphine as a painkiller, preventive medicine and psychiatric treatment were advances that changed health care forever.

During World War II, there was another severe nursing shortage in the United States because many volunteered for military duty. Working under the supervision of registered nurses, practical nurses provided hands-on care and made it possible to treat more patients. From this, the concept of delivering nursing care as a team developed.

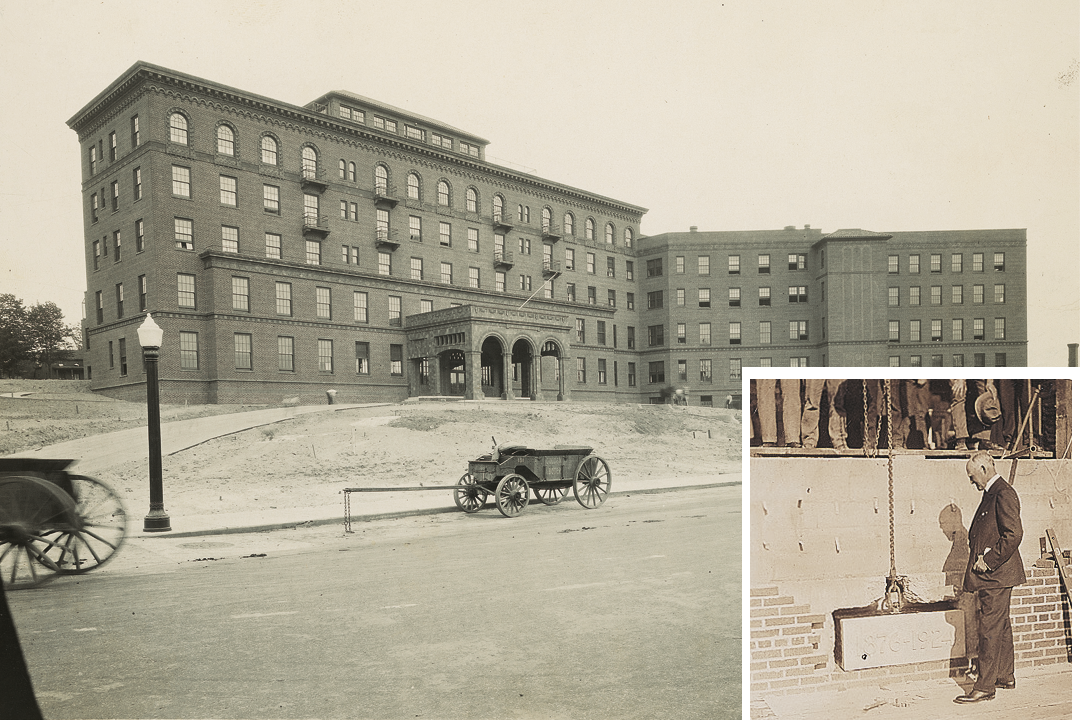

The decision was made to construct a new hospital. With the increased workload, hospital trustees hired a supervisor with both medical and executive training: George Park, MD.

Albert Stickley provided Butterworth Hospital with its first ambulance.

A medical library was established and later named for its benefactors. Julius Amberg and his son David were lawyers who served many terms on the Butterworth Hospital Board of Trustees.

A new clinical laboratory was added.

Edward and Susan Lowe donated money and the building site of the new hospital, which totaled nearly $1 million in contributions. As her personal gift, Susan Blodgett Lowe donated the wood paneling in the hospital.

The Butterworth Hospital School of Nursing training program was extended to three years.

The cornerstone was laid for the new building in 1924.

The new hospital housed 200 beds, 50 bassinets, and a 12-bed ward and playroom for pediatric patients.

Formal internships began in 1919. Physicians were trained under a rotating program that remained unchanged until the late 1930s.

The old hospital building was converted into the new Kendall Home for Nurses.

An eye clinic and a dental clinic were established.

A department of social services was created.

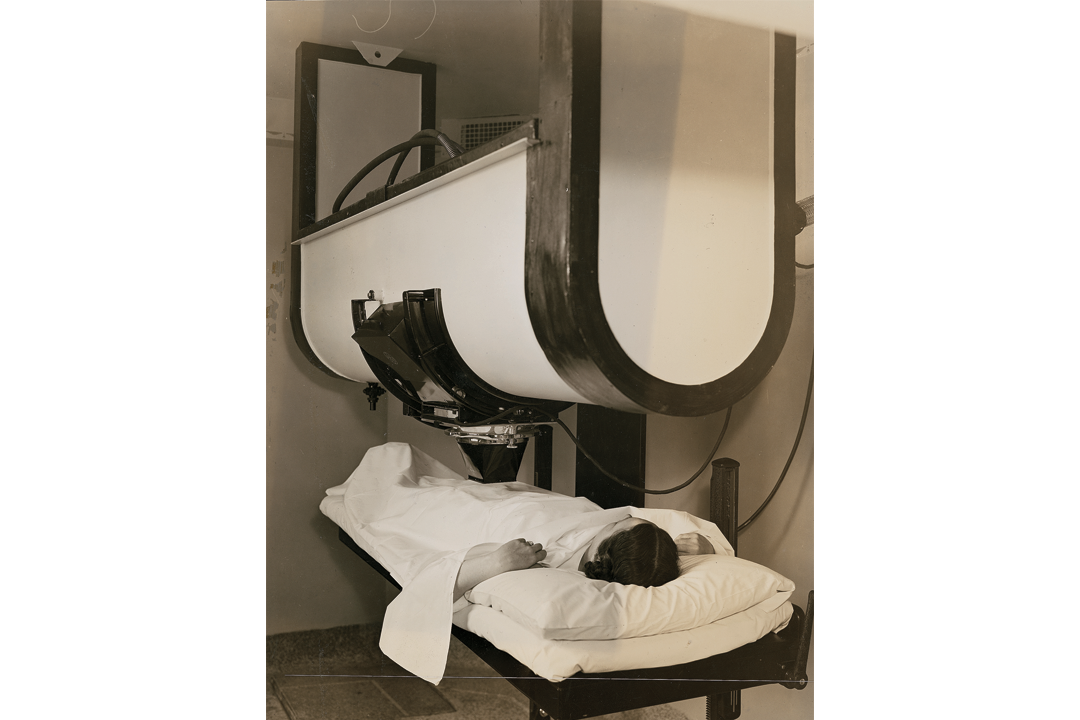

Anton G. Hodenpyl bequeathed $250,000 for new X-ray, physical therapy and radium equipment, and to refurbish the Kendall Home, Golden Rule Cottage and cafeteria.

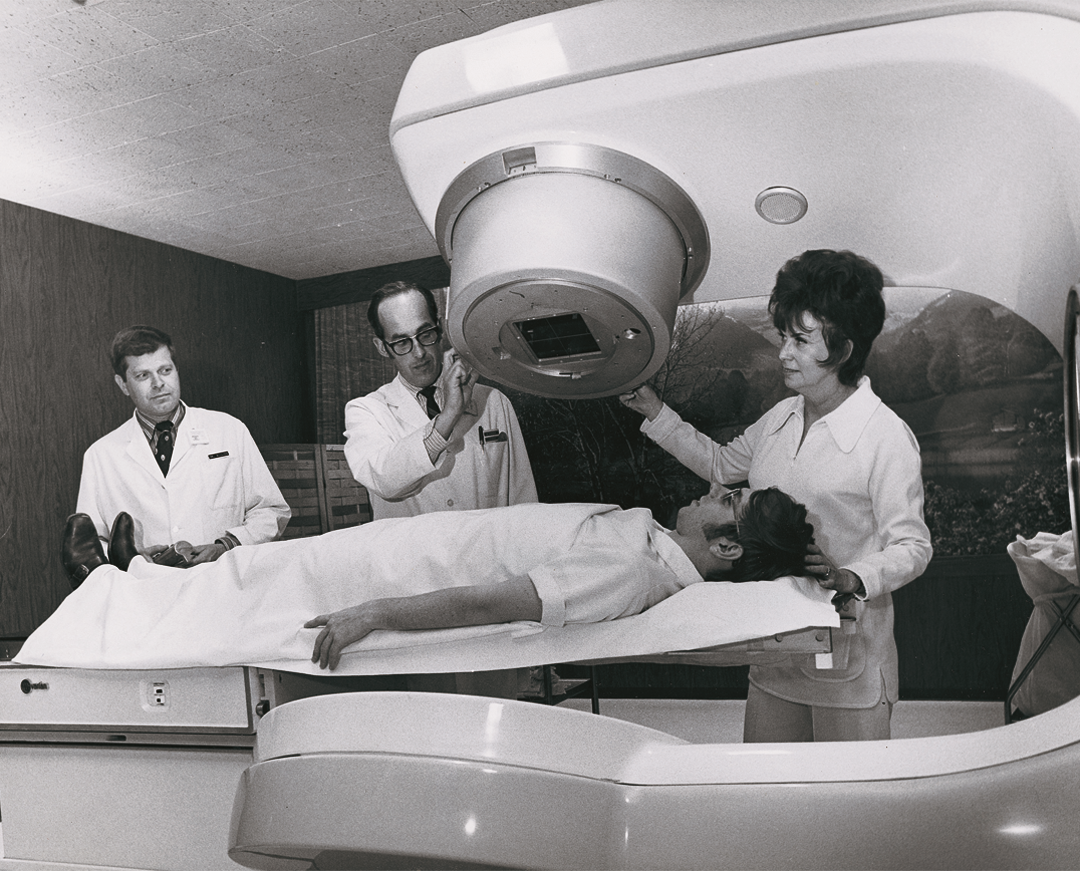

Butterworth Hospital became the eighth hospital in the United States to obtain a deep radiation therapy unit to treat cancer patients.

The hospital acquired its first electrocardiograph machine.

The first students were admitted to the new residency program in surgical and internal medicine.

The National League for Nursing Education accredited the nursing program at Butterworth Hospital, one of 72 in the nation to be selected.

Because of the war, the hospital's medical and nursing staff was reduced by 40 percent. Eighty staff members were serving in the armed forces.

Butterworth Hospital and other hospitals in Grand Rapids coordinated with the Red Cross and the Office of Civil Defense to organize a field and hospital disaster medical service.

Trustees of the hospital authorized the purchase of equipment to establish a blood bank.

The Frances Payne Bolton Act created the United States Cadet Nurse Corps as a means to recruit students into nursing schools. Butterworth Hospital expanded enrollment to 250 students. With the aid of volunteers, these students provided almost all of the nursing care during the war.

Medical staff bylaws were amended to allow physicians to practice at Butterworth Hospital, regardless of their affiliation with other hospitals.

World War II ended and the hospital again experienced a nursing shortage as many nurses returning from the war preferred to devote themselves to their home and family.

The Butterworth Hospital School of Medical Technology was established by Paul Van Pernis, MD, the hospital's only pathologist.

The community's demand for services continued to grow post-war. Butterworth Hospital saw 13,344 patients in 1947. More than 2,640 babies were born at the hospital, an increase of 57% from the previous year.

Kendall Home for Nurses was converted into six separate apartments for residents and their families.

The United Hospital Building Fund was established for Butterworth, Blodgett and St. Mary's hospitals with a campaign goal of $3,905,000. Plans began for future expansion of all the facilities to better meet the needs of the growing community.

1951-1980

Specialization Advances Care

After 1950, many of the most feared infectious, epidemic diseases were eliminated. American hospitals were now modern scientific institutions, valuing antiseptics and cleanliness and using medications for pain relief. Between 1950 and 1970, the medical work force tripled to 3.9 million people—more than the steel industry, the automobile industry and interstate railroads combined.

As medicine became more complex, doctors grew more specialized as practitioners. Because new medical procedures took more time, physicians delegated more responsibilities to nurses. By 1980, advances in new treatments, surgical procedures, drugs and technology dramatically changed health care delivery.

Following a successful fundraising campaign, the hospital initiated expansion of its facilities with a new west wing.

The new west wing included 155 additional patient beds, a new surgical suite, central supply, a dietary department and an expanded laboratory.

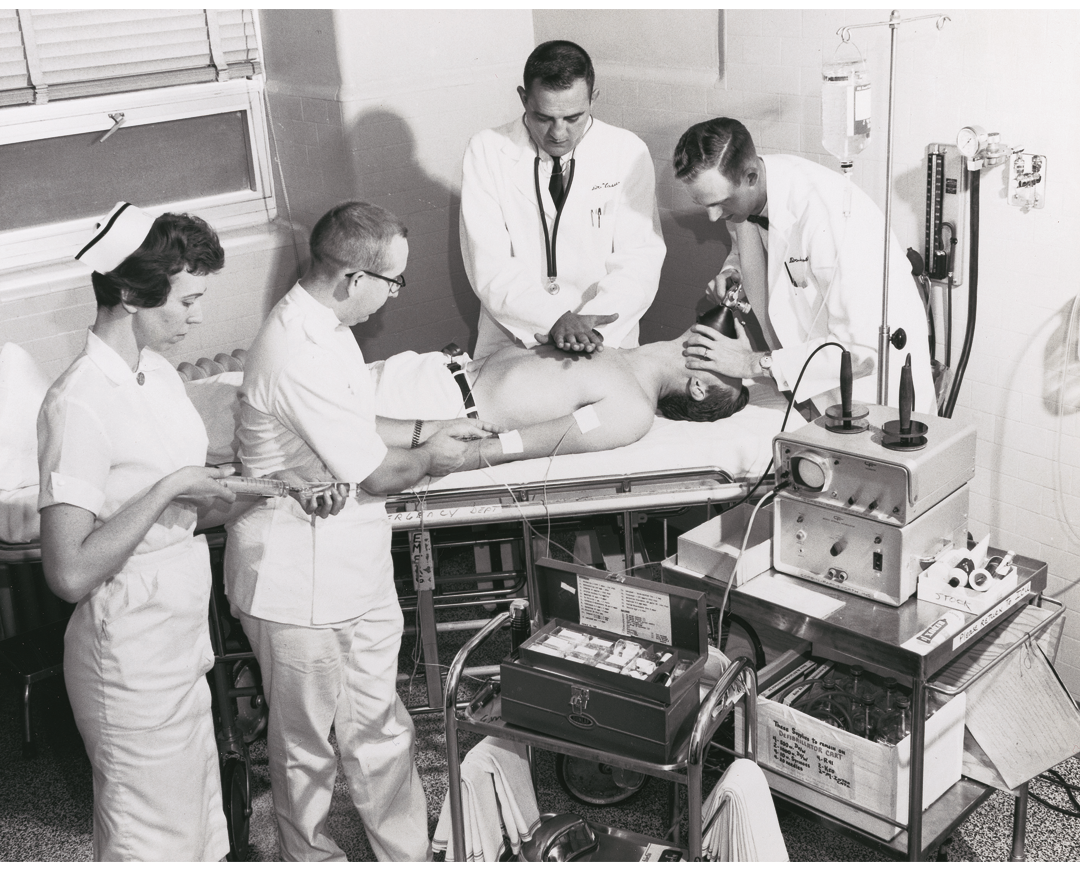

Butterworth Hospital became the first hospital in West Michigan to own a defibrillator. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was now taught to medical and nursing students.

M. Annie Leitch, RN, director of the Butterworth Hospital School of Nursing, left after sixteen years to serve a two-year term as president of the American Nurses Association. Ms. Leitch was a highly respected administrator who was a progressive and energetic advocate for nurses.

New construction changed the main entrance and the address for Butterworth Hospital from 300 Bostwick Ave. NE to 100 Michigan St. NE.

The isotope laboratory was created for the treatment of thyroid and cardiac disorders.

The first Cobalt-60 radiation therapy unit was installed, the third such unit in Michigan.

Larry Birch, MD, was the first appointed director of medical education and was instrumental in expanding the hospital's internship and residency programs.

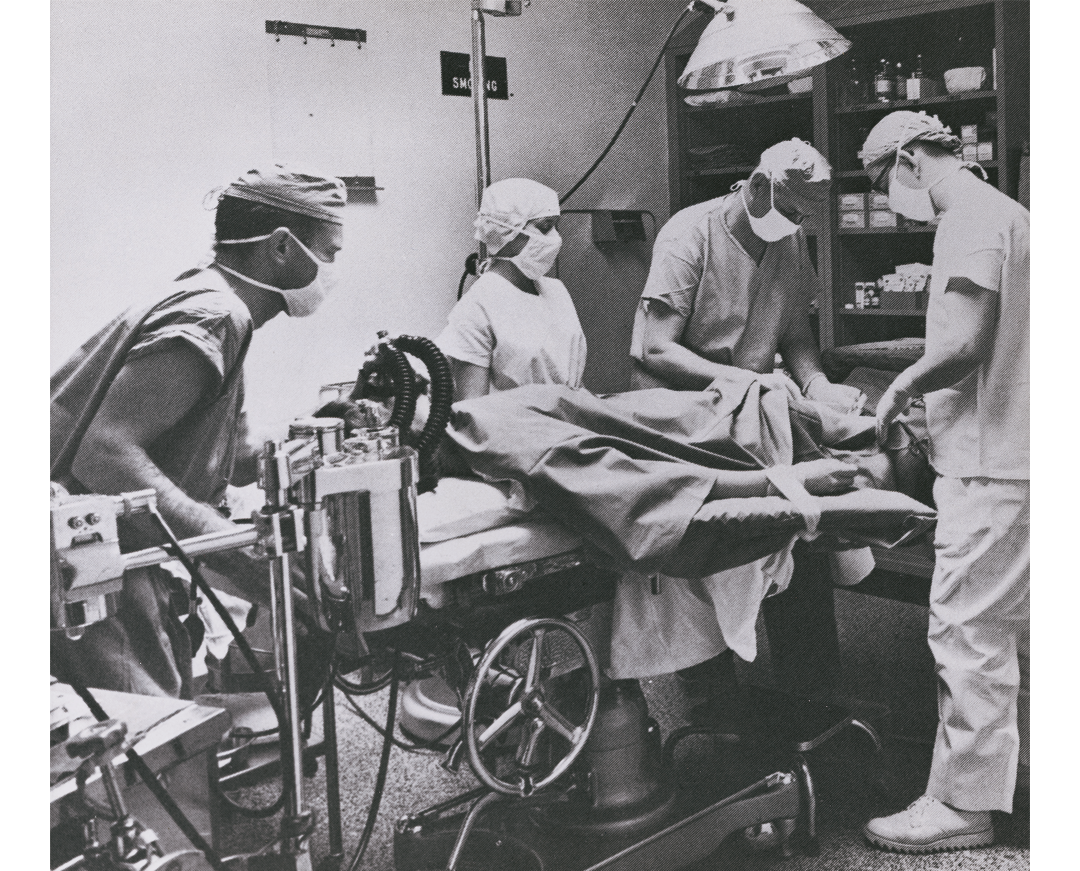

Butterworth Hospital became the first hospital in the United States to perform outpatient surgery.

The cardiac catheterization laboratory opened.

Kendall Home for Nurses was leveled to build a new nursing residence.

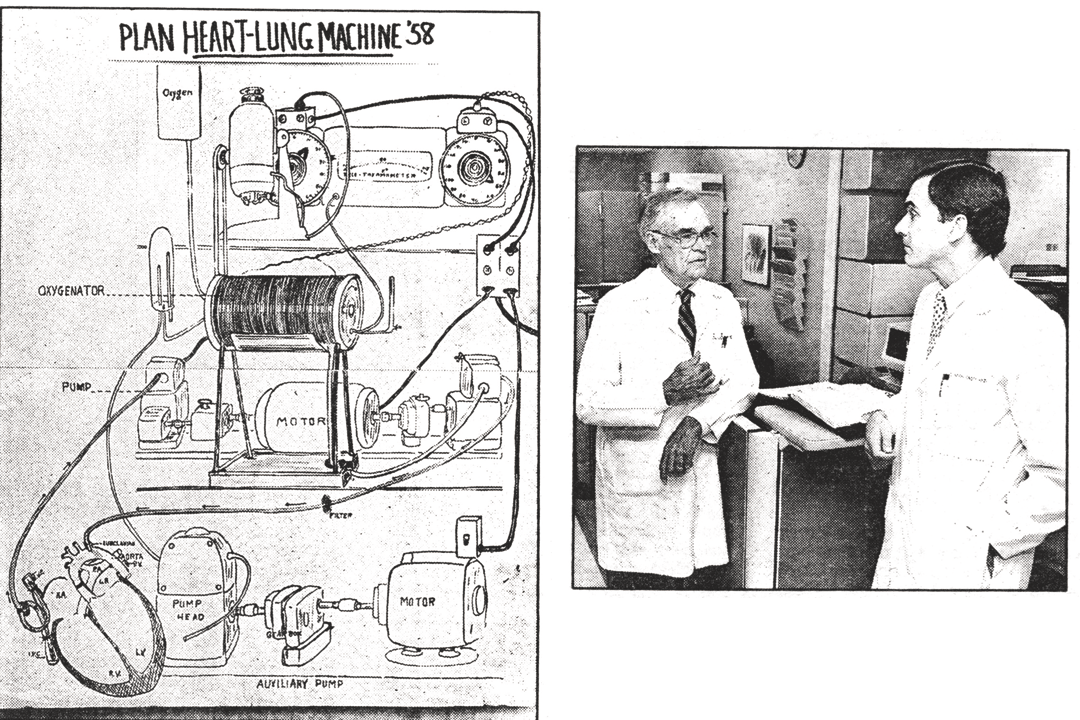

The first open heart surgery at Butterworth Hospital was performed by Leo Kenney, MD, and R.J. Schlosser, MD. The heart-lung machine was set up by Luis Tomatis, MD, a process that originally took seven hours.

The south addition was completed and included outpatient clinics and a refurbished emergency department.

The east addition included an eight-bed pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), a new playroom, an expanded nursery, and suites for labor and delivery.

The hospital acquired its first computer, which occupied nearly all the space in one office.

After renovations were complete, there were 467 patient beds. Smaller wards replaced the old 16-bed wards and oxygen was piped into every room. Pneumatic tubes connected nursing stations with the lab, pharmacy and other departments.

Pathologist Joseph Mann, MD, published his discovery of the Xga blood group factor, the only sex-linked factor, in “The Lancet,” a prestigious medical journal founded in 1823. Blood group factors provide genetic information for blood typing.

The Oral Cleft Clinic was opened in partnership with the Division of Speech Pathology at Western Michigan University and sponsored by the March of Dimes.

The hospital purchased a Sarns™ Pump Oxygenator Console to use during open heart surgery that reduced the amount of blood needed from 17 pints to four.

William L. Johnston, MD, and his wife, Beverly Johnston, established the fine art collection. Today, with more than 1,200 pieces, it is one of the largest collections of its kind in the United States. Dr. Johnston believed that art played a critical role in healing and wanted to share it with others.

A new cancer fighting machine, the linear accelerator, replaced the cobalt therapy unit.

The hospital again expanded to include new laboratories, a 325-seat auditorium, a new surgical suite, intensive care units, a gift shop and a snack bar.

Butterworth Hospital celebrated the 100th anniversary of St. Mark's Home and Hospital.

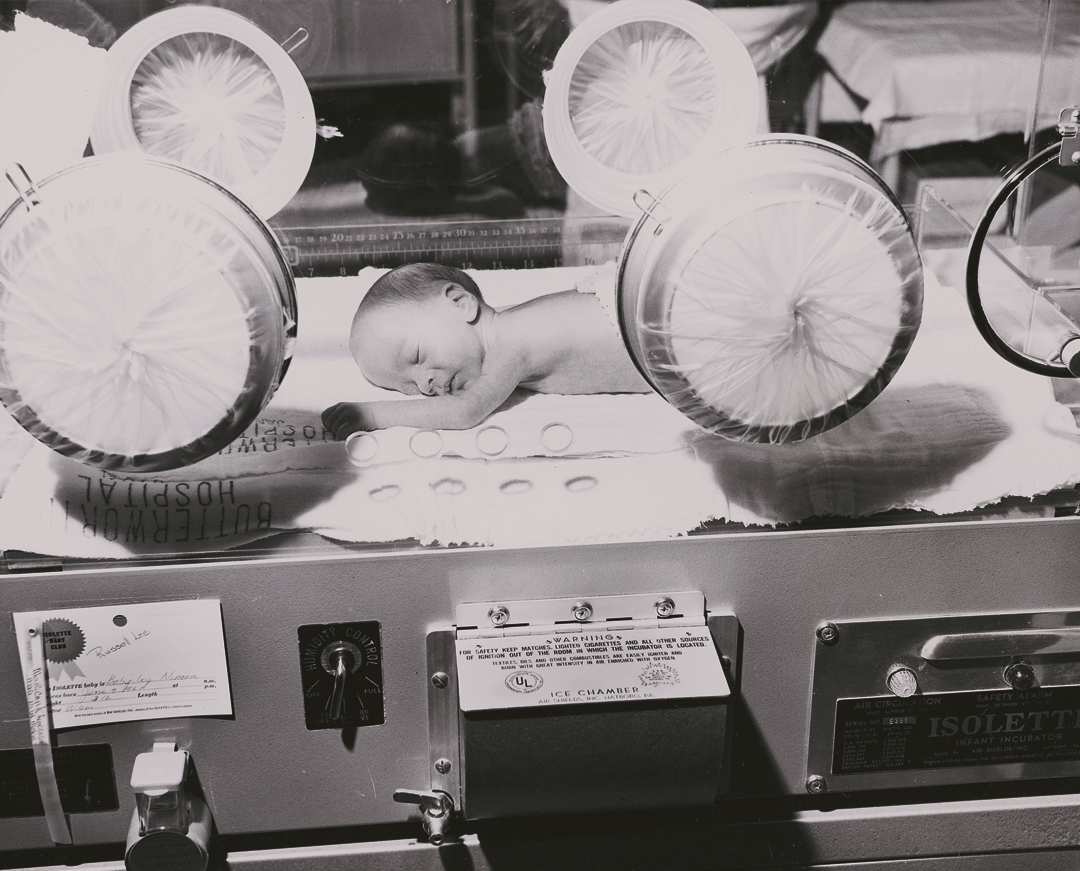

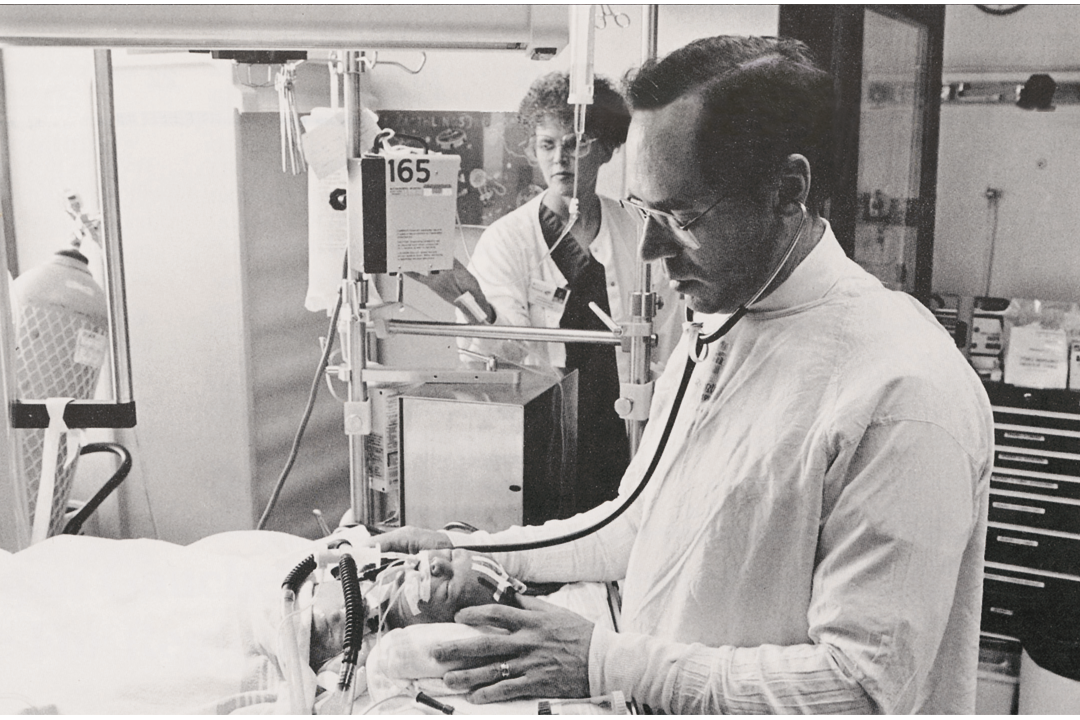

With $100,000 in donated funds from Gerber® Baby Foods Fund the first neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in West Michigan opened.

The neonatal transport team was created to safely bring high risk newborns from other hospitals to the NICU.

The Butterworth Hospital Pacemaker Clinic opened, which offered patients the option of checking their device by telephone instead of visiting the clinic.

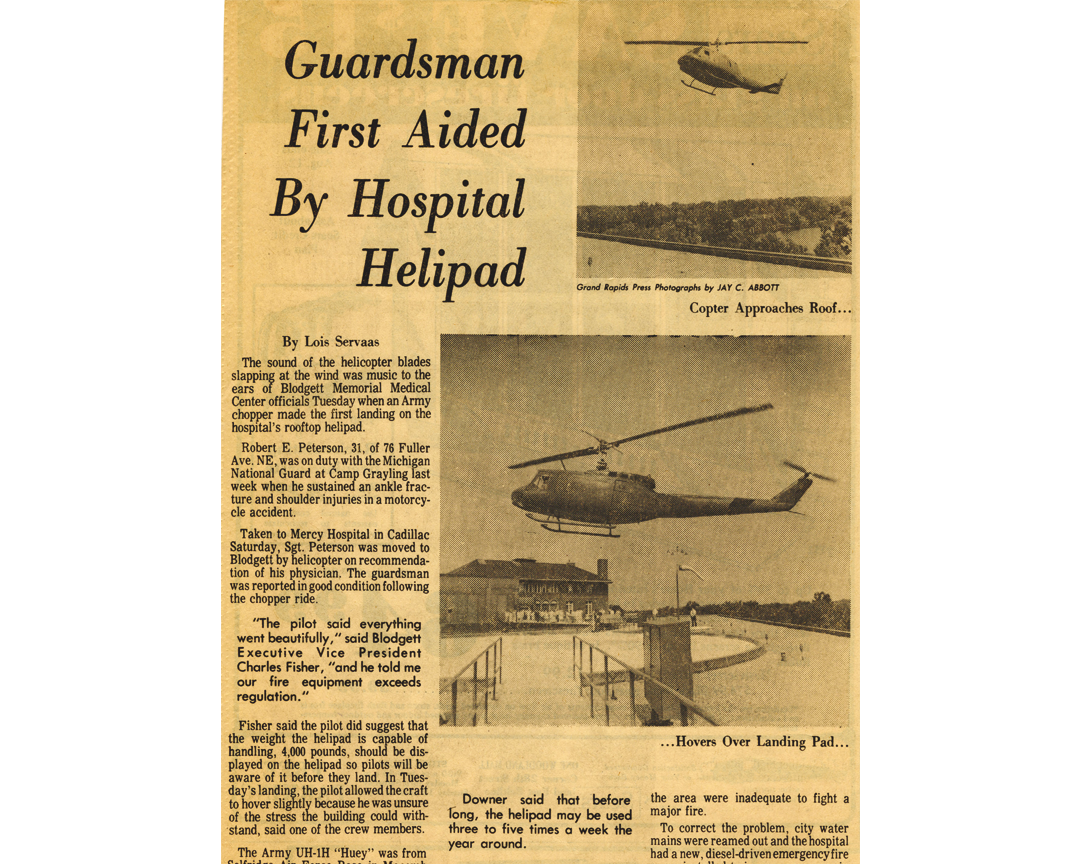

A helicopter landing pad on the roof of the hospital was completed.

The National Cancer Institute awarded the clinical oncology program a planning grant to develop a national model for community programs.

The next phase of the building program included a new six-level tower with three patient floors and new facilities for radiology, nuclear medicine, outpatient clinics, social services, outpatient surgery and the emergency department.

The Grand Rapids Clinical Oncology Program, a partnership with Blodgett Memorial Medical Center and St. Mary's Hospital, was housed at Butterworth Hospital.

Butterworth Hospital's Emergency Department was designated as a trauma specialty unit.

The Ambulatory Care Center opened, which housed the oncology day surgery unit.

1981-1996

Reshaping Health Care Delivery

In 1980, the World Health Organization declared that smallpox had been eradicated. The following year, the first case of HIV in the U.S. was identified. Use of technology exploded with the personal computer, telemedicine, invention of the artificial heart, and use of ultrasound and lithotripsy to remove kidney stones.

Later in the decade, laser technology impacted heart procedures and the first liver transplant from a live donor was performed. Genetic engineering was used to learn more about human biology and manufacture products such as insulin.

The rising cost of health care forced cost-cutting practices such as obtaining tests or procedures outside the hospital setting. With the growth of outpatient procedures, reduced insurance payments and the growing number of Americans without health insurance, hospitals were forced to be more competitive.

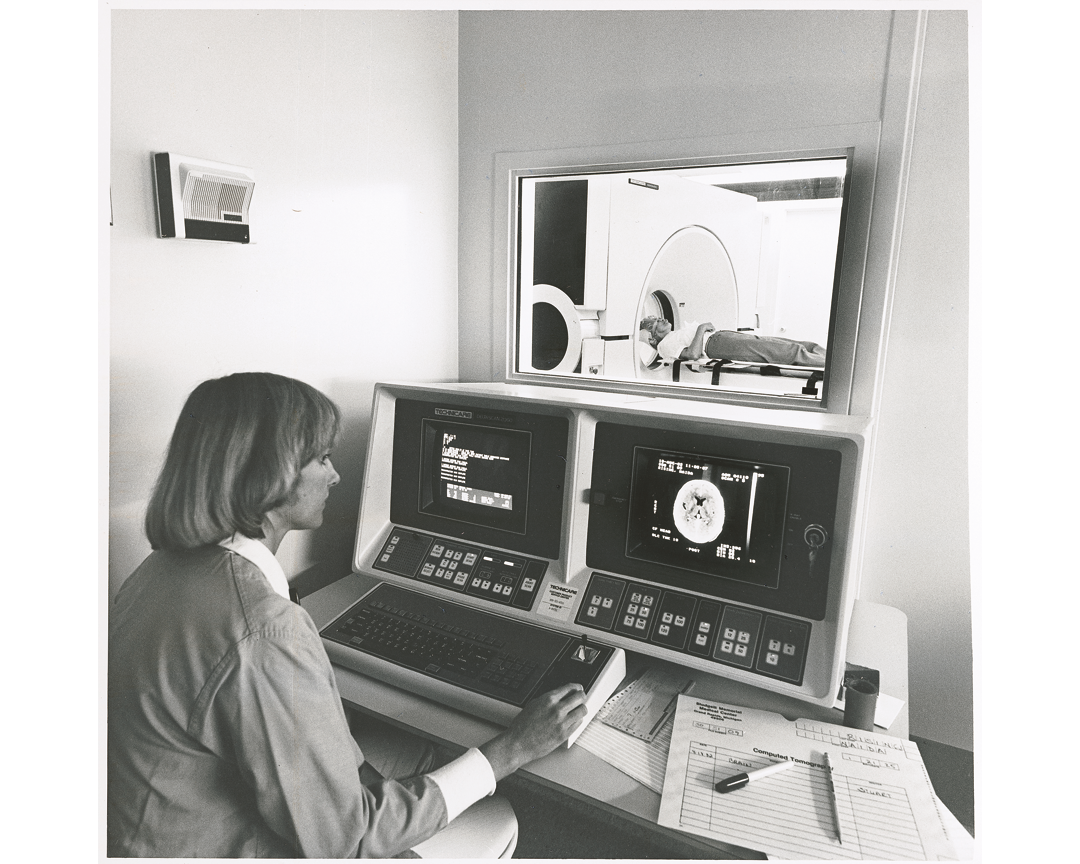

The first computerized tomographic (CT) scanner was purchased and installed at Butterworth Hospital.

The clinical nutrition laboratory is established to conduct studies on long-term effects of Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN), intravenous feeding that bypasses the usual process of eating and digestion.

The first hyperbaric oxygen chamber in Grand Rapids is installed to treat patients for air embolisms, carbon monoxide poisoning, infections and wound care.

A nursing care delivery system called the Clinical Practice Model is implemented. Delivery systems identify who has the accountability for nursing care and clinical outcomes, and ensure higher quality of care.

The Butterworth Hospital School of Nursing closes after 95 years—the result of a national move toward degree nursing programs.

The Western Michigan Brain Injury Network, a unique partnership between Butterworth Hospital, Mary Free Bed Hospital and Rehabilitation Center, and Hope Network was formed to offer full rehabilitation services to those with brain injuries.

The Butterworth Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) begins with three employer groups.

Aero Med helicopter service transports its first patient.

Butterworth Hospital established the West Michigan Stone Center.

A lithotripter, one of only five in the state, was installed for treatment of kidney stones. The hospital also pioneered a program for extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) procedures.

Health Connections, an educational resource center for women and children, was established.

The Sleep Disorders Center opened and treated 148 patients in its first year.

The Butterworth Foundation is incorporated as a non-profit corporation.

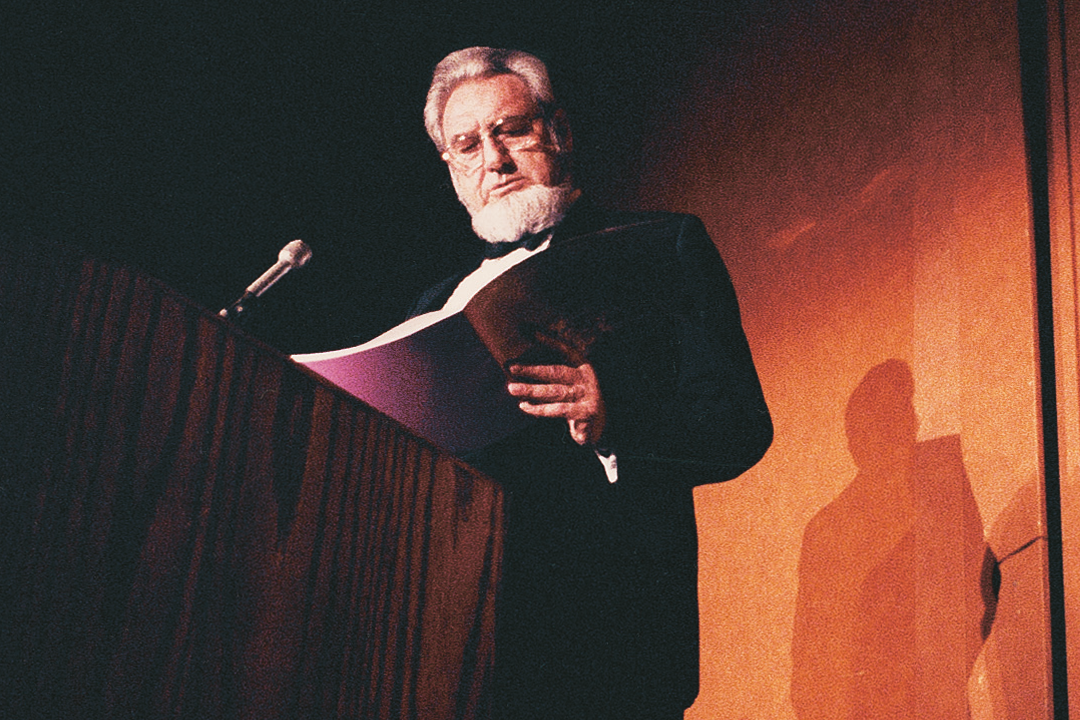

Butterworth Foundation sponsors its first Gala which is hosted by C. Everett Koop, MD, who served as thirteenth Surgeon General of the United States from 1982 to 1989.

ASK-A-NURSE® is established. During the first year, RNs helped more than 50,000 callers find answers to health-related questions.

The hospital participated in several national research studies that used Exosurf to treat adults and neonates with Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS).

Butterworth Hospital added the Storz Modulith SL20 Lithotriptor which offered treatment for both renal and biliary stones.

The American College of Surgeons verified Butterworth Hospital as a Level 1 Trauma Center.

The Mothers Offering Mothers Support (MOMS) program was launched.

West Michigan Laser Center surgical center opened at Butterworth and required training for more than 160 physicians and 80 nurses.

Butterworth and Western Michigan University developed a surgical training program for physician assistants.

The first pediatric patient is treated through the Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) program. The procedure involved placing the patient on an artificial lung and can be made to operate for several days at a time.

Richard and Helen DeVos donated $5 million and the 10-story center tower was renamed the Helen DeVos Women and Children's Center.

Peter C. and Pat Cook pledged $2 million for the Health Sciences Research & Education Institute which established Butterworth Hospital as a major teaching and research medical facility that included expansion of existing library and technology services.

The Butterworth Hospital Pediatric Cardiovascular Surgery Team was formed to care for patients with heart birth defects, the first of its kind in West Michigan.

The hospital received a Frey Foundation grant to initiate funding for Child Life Services, a program to provide therapeutic, diversional play for patients, siblings and parents.

Butterworth Hospital celebrated 100 years of service to the community.

The pediatric surgery expansion included the addition of a new reception/holding area, induction rooms and four new operating rooms.

The first West Michigan Chapter of “Operation Smile” surgery was completed on an 18-year old woman from Kiev, Ukraine.

The Visiting Nurse Association celebrated 100 years of service and became a member of Butterworth Health Corporation.

The Continuing Care Group was established.

The Lettinga Cancer Center was established, which was named in recognition of a major gift from Bill and Sharon Lettinga.

1846-1914

Caring For Those in Need

It began with a group of women who came together to form the first charity in West Michigan. Their giving spirit responded to the events of the day by caring for the poor and hungry, and eventually those in need of medical care.

The Civil War challenged the mission of the early philanthropists. They were asked to help care for injured soldiers in tent hospitals established throughout the area. This temporarily took them away from their charity work, but refocused them on providing health care services after the war.

During this time, one English physician was revolutionizing the practice of medicine. Colleagues of Baron Joseph Lister, MD, made jokes about some of his more peculiar habits: washing his hands before touching patients, heating instruments to sterilize them and using carbolic acid as an antiseptic. They stopped laughing when Dr. Lister's patients lived while theirs died.

Women from area churches formed a charitable union, the first philanthropic organization in West Michigan. They agreed to pool their efforts to help feed, house and clothe the neediest among them.

The Female Union Charitable Association was created.

The association bought its first building near the corner of LaGrave Avenue and Oakes Street, which allowed the women to take in orphans. They changed their name to the Grand Rapids Orphan Asylum and Ladies' Union Benevolent Association.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Grand Rapids became a headquarters for Union troops. The women of the Grand Rapids Orphan Asylum and Ladies' Union Benevolent Association responded by sewing uniforms for the soldiers. As the war dragged on and the casualties soared, the women also were called upon to help care for wounded soldiers. Reluctantly, they gave up their orphan asylum.

After the war, the women rededicated themselves to caring for the poor and the sick. They renamed their organization the Ladies' Union Benevolent Society.

The society shortened its name to the Union Benevolent Association, after including men for the first time to help run the organization.

The Union Benevolent Association moved to a new location at Lyon Street and College Avenue.

The association decided to create a nursing school in Grand Rapids.

Five proud young women, shown at left with the school's superintendent, were capped as the first graduates of the Union Benevolent Association Training School for Nurses.

The Union Benevolent Association's first medical staff members were appointed and Charles Shepard, MD, was named the chief of staff.

With the addition of a new operating room, obstetrics unit and children's ward, the Union Benevolent Association was now a full-fledged hospital with the sole function of caring for the sick and injured.

John Wood Blodgett Sr. joined the association's board of trustees, later becoming chairman. His involvement changed the future of the association forever.

In an interview with the physician when he was in his late 60s, Richard Root Smith, MD, recalled how medicine was practiced in 1892 when he was an intern.

"The carbolic acid spray era of antiseptics had passed and we were in the so-called era of aseptic surgery. Hospitals in those days were simply large houses with the addition of an operating room. There was no laboratory. A bathroom similar to one found in any private home served for all toilet facilities.

Doctors operated without masks. They were often bearded and mustached. We operated without gloves, our hands bare. It was not until about 1905 that gloves were worn. First we wore cotton, then rubber."

John Wood Blodgett Sr. and his wife, Minnie Cumnock Blodgett, donated land and money to the Union Benevolent Association to build a new hospital. The facility would be named Blodgett Memorial Hospital as a tribute to John's late mother, Jane Wood Blodgett.

1915-1958

Modern Medicine Emerges

In the early 1900s, the average hospital stay was 14 days and the cost was $45. The most common illnesses being treated were typhoid, tuberculosis (first called consumption), dysentery and diphtheria. From 1918 to 1919, an epidemic of Spanish flu spread across the United States, filling hospital beds. In two years, the flu killed 500,000 people nationwide.

World War I strained the resources of Blodgett Memorial Hospital. Physicians from Grand Rapids were organized into a military hospital, designated as Unit Q and headed by Maj. Richard Root Smith, MD. They were sent to France where they spent almost a year outside Paris running a military hospital. World War II spurred advancements in medicine such as open heart surgery and new medications like penicillin. After the war, there were three times as many babies born than had been a decade before. The influx kept all of the hospitals in Grand Rapids busy.

A reporter from The Grand Rapids Press toured the new Blodgett Memorial Hospital, which was nearly complete. In the article, he noted: "'Finest in the world' is an ambitious and comprehensive term used every day in loose fashion. Yet this is the best literal description of the new hospital building now nearing completion."

Blodgett Memorial Hospital opened its new facility at the corner of Wealthy Street and Plymouth Avenue.

The hospital modernized its services, offering an obstetrics unit with 35 beds and 30 bassinets inside the hospital rather than in a separate building. This change helped reduce infections. In its first year, the obstetrics unit delivered 126 babies.

While most babies were still delivered at home in 1916, three kinds of mothers came to Blodgett Memorial Hospital: those who could afford the best care, those too poor to have adequate delivery space at home, and those with complications requiring specialized equipment and medical staff.

The first pediatric services at Blodgett Memorial Hospital were organized by Dr. Thomas Gordon.

The first physician interns came on staff, and Blodgett Memorial Hospital launched its nationally recognized medical education program.

William J. Mayo, MD, one of the original Mayo brothers from Rochester, Minnesota, came to Grand Rapids for the opening of a physician clinic on the corner of Wealthy Street and Plymouth Avenue. It was designed to become the second Mayo Clinic. However, the publicity hurt more than it helped by stirring professional jealousies among other physicians. Hostility from area doctors, the stock market crash and the subsequent Great Depression brought about the end of the clinic in 1934.

Ronald Yaw joined Blodgett Memorial Hospital as assistant administrator. In 1940, he became director of the hospital, a position he held until 1974.

Battlefield trained, Richard Rasmussen, MD, returned from active naval duty to perform West Michigan's first successful aortic splice on a little girl at Blodgett Memorial Hospital. The first such surgery - cutting out a piece of congenitally narrowed aorta - had been done only four years before in Sweden.

So many children were hospitalized with polio that Blodgett Memorial Hospital had to close its west entrance, and convert its admitting area and administrative offices into an emergency room.

A new addition opened with 130 more beds. The space accommodated the influx of heart patients triggered by Dr. Noyes Avery's Cardiac Study Group. This was the same year Dr. Avery performed the first heart catheterization in West Michigan.

Richard Rasmussen, MD, and Clair Basinger, MD, visited clinics in Cleveland and Minneapolis where researchers were ahead of manufacturers and had built their own heart-lung machines. The two cardiac surgeons made notes, took pictures, bought parts and descended into Dr. Rasmussen's basement where they began building. When their prototype heart-lung machine was complete, it was so big they had to demolish a wall to get it out of the basement.

On November 11, 1958, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Basinger used their own heart-lung machine to complete the first open heart surgery west of Ann Arbor.

Blodgett Memorial Hospital opened one of the first intensive care nursing units in the country, offering around-the-clock care for critically ill patients.

1959-1996

Leading in Excellence and Innovation

Health care was becoming more sophisticated and costly. Facilities continued to expand, and more staff and physicians were needed. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law health insurance for all Americans 65 years and older, called Medicare. In 1966, hospitals in Grand Rapids mutually agreed to start all full-time nurses at $6,000 a year. Wages and salaries were 70 percent of operating costs, which required hospitals to raise rates for patients. In addition, the Vietnam War caused a nursing shortage at home.

Significant advancements in techniques and technology pushed Blodgett Hospital to the forefront of health care in the region, state and country. An increase in outpatient services, the introduction of laparoscopic surgery and more precise radiology equipment meant better, more convenient health care for patients in West Michigan.

Blodgett Memorial Hospital was the first in the area to perform heart surgery on the upper chambers of the heart, saving the life of a 12-year-old boy.

Alfred Swanson, MD, a pioneer in hand surgery and a physician at Blodgett Memorial Hospital, developed silicone implants to use for joint replacement surgery and became internationally known for his expertise.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Blodgett Memorial Hospital orthopaedic surgeon Charles Frantz, MD, to advise doctors in Germany on how to treat the 5,000 German babies born with deformities from Thalidomide, a drug taken by pregnant mothers. Dr. Frantz devised the classification system for diagnosing children born with limb malformations.

Blodgett Memorial Hospital, Butterworth Hospital and Saint Mary's Hospital formed the Grand Rapids Area Medical Education Center to coordinate clinical training for third- and fourth-year medical students, most of them from the new medical school at Michigan State University.

A $27 million building and remodeling package included a three-story professional building and four-level parking ramp for 1,200 cars. No beds were added, but the renovation was needed to bring the buildings from 1953 and 1962 up to code.

Blodgett Memorial Hospital was renamed Blodgett Memorial Medical Center to reflect the broad array of medical services provided, including the newly opened Regional Poison Center.

The area's first rooftop heliport for transporting critically ill patients was installed.

The West Michigan Burn Unit opened thanks to a $700,000 gift from the Grand Rapids Jaycees.

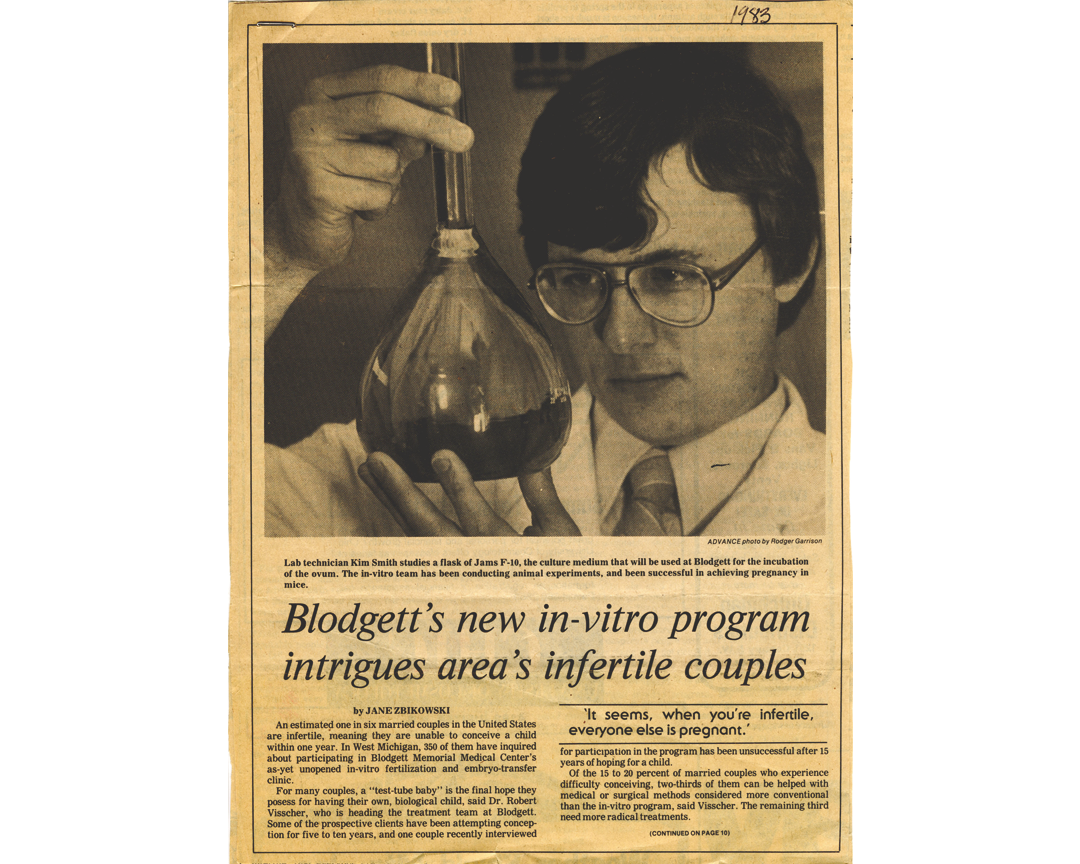

Robert Visscher, MD, developed one of only three in vitro programs in the country at this time. The program produced Michigan's first set of twins conceived outside the mother's body. The babies came six weeks early to a couple from Bay City, Michigan, and made headlines across the country.

Cardiologists Ray Fuller, MD, and Robert Davidson, MD, spearheaded the opening of West Michigan's most extensive cardiac catheterization lab, which was used for balloon angioplasty to unclog narrowed arteries.

Blodgett Memorial Medical Center's first fellowship-trained neonatologist, Charles Winslow, MD, was hired to run the special care nursery.

The Betty Ford Center for Cancer Prevention and Screening opened, focusing exclusively on breast cancer care.

The 99th and final class of nurses graduated from the school of nursing. The nurses' training was upgraded to a college-degree program. Students at Grand Valley State University continued to do their clinical training at area hospitals.

Blodgett Memorial Medical Center was the first in West Michigan to use laser angioplasty to open blocked arteries in the leg.

A state-of-the-art 3-D computed tomography (CT) scanner was installed. At the time, this technology (Somatom Plus) was only available at three other sites in the country.

Also in 1989, Oliver Grin, MD, orchestrated the opening of the only neuroscience intensive care unit in the city.

Blodgett Memorial Medical Center was the first in West Michigan to have a laser for laparoscopic surgery.

It also became one of the first hospitals in the country to use coronary atherectomy to remove plaque from the arteries.

The state's first mobile cardiac catheterization lab was introduced. Instead of the hospital's out-of-town patients driving to Grand Rapids for the procedure to diagnose heart disease, the 450-foot catheterization lab on wheels went to cities like Hastings, Cadillac, Big Rapids, Alma, Reed City and Manistee.

Also in 1992, Blodgett Memorial Medical Center merged with Ferguson Hospital, which specialized in colon and rectal diseases, to form the premier Ferguson-Blodgett Digestive Disease Institute.

A letter of intent was signed with the trustees of Butterworth Health Corporation to merge the two hospitals. United by the goal of saving money through reduced duplication and greater efficiency, the hospitals went from being arch competitors to partners.

Interventional neuroradiologist N. Thomas Peterson, MD, was the first in the area to use a Guglielmi Detachable Coil on an inoperable brain aneurysm. Dr. Peterson inserted the micro coil into the ballooning aneurysm to isolate it from the patient's circulatory system, where its thinned walls could pop and cause a fatal brain hemorrhage.